'Abducting A General' and SOE in Crete.

Generals and Coastal Posts:

There are several early references in SOE records suggesting plans to kidnap a General and also a German coastal command post.

Dunbabin identified this in his first Report, dated May 16th 1942:

‘The most effective morale raiser would be the seizure of a German coast watching post. This should appear to be an entirely outside job, and for preference, should take place outside the area of our regular operations.’[1]

It would appear that – in his 3rd Report [2]- Dunbabin hoped to kidnap the Tris Ekklisias post on the night of his evacuation – 15th February 1943 – but this proved too complicated to organise.

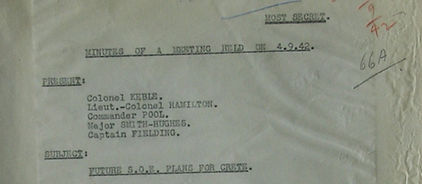

The Minutes of a meeting held in Cairo on the 4th September 1942 offer the first mention of kidnapping a General.

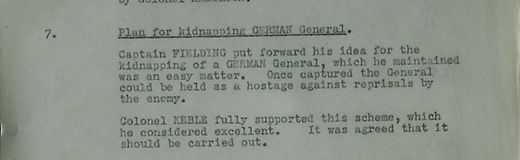

‘Plan for kidnapping German General.

Captain Fielding put forward his idea for the kidnapping of a German General, which he maintained was an easy matter. Once captured the General could be held as a hostage against reprisals by the enemy. Colonel Keble fully supported this scheme, which he considered excellent. It was agreed that it should be carried out.’[3]

In the Official Report on SOE in Crete[4] Dunbabin refers to late November 1942, just as the fortunes of the Allies were turning in their favour after the success at El Alamein.

‘Captain Fielding returned to Crete on the 27th November 1942, making a blind landing from a submarine on the Selino coast and thus forming his first contact with an area which became one of the main centres of British activity. Captain Fielding had a plan to kidnap the German Commanding Officer, General Andrae, and hold him as a hostage. This came to nothing because Andrae was replaced by General Brauer, who was more cautious in his movements and because, on the Prime Ministers order, counter-atrocities were forbidden and the principle of post-war trial of war criminals substituted. Another plan in the air at the time was the capture of a German coastal post, in such a way that it would appear to be the work of Commandos.’

Leigh Fermor considered the challenges of kidnapping a German coastal post and recorded his planning and views in his 3rd Report (April to June 1943). His conclusion was that capturing a post at the same time as organising the arrival of a motor launch from North Africa with the attendant demands of organising the evacuation and arrival of agents and Cretans was too complex and that both tasks risked jeopardising the other.[5]

The first direct reference to kidnapping a General from reports from the field occurs on the 6th July 1943[6], when Fielding wrote to Jack Smith-Hughes and asked: ‘would you send a boat in at a moments’s notice if I arrange to get Brauer?’

He goes on to say, in reference to capturing a post:

‘I plan to take the Ayia Roumeli post – subject to your approval and my future recce. Would you be prepared to send in a boat for this or shall I have to kill the lot? PLEASE ANSWER.’

Fielding elaborates on the plan for kidnapping Brauer at the end of his report of 11th July 1943. [7]

Appendix A; The case of General Brauer.

‘…ISLD[8] have openly suggested the possibility of abducting the General and after finding me in agreement with the plan are renewing these suggestions more forcibly.

At the moment our joint plan is for ISLD to make the necessary enquiries, preparations and r.v. and, when these are all settled, for SOE to do the dirty work. This collaboration is reasonably sound as the ISLD members would be unable to carry out the plan while I without them would not have the necessary information on which to act.’

The next reference occurs a few weeks later – again from Xan - in a letter dated 28th July 1943 to Jack Smith-Hughes, head of the Cairo office of SOE. The letter indicates the vicissitudes and the risks of the BLO life on the island at the time. By this time Xan had been on the island for 8 months.

‘Dear Jack

I suppose it’s nobody’s fault about the ship’s hoodoo but I’d first like you to know what prompted me to send whatever bad-tempered messages I have sent.

The journey from the station to the beach is by far the toughest of the many tough marches I’ve had to do this year. It’s a five hour climb down straight over cliffs, as for security reasons I have to avoid the villages; in many places a man can only get along on all fours. I have to go down heavily loaded with food and water. Even so we can’t carry enough water to last us all the night and we have a grilling tortuous seven hour climb back. It would be bloody enough for a man in good condition to undertake this journey just once – and for some purpose. As you know I’m fairly tough on the road. But there’s a limit to everyman’s physical endurance. I’ve just about reached mine.

In addition, of course, the undertaking becomes more perilous with each fresh postponement. The Huns have cottoned on to that strip of coast and we had a nasty few hours on the 18th.

It’s obvious to me now that capturing Generals or coastal posts is out of the question as long as storms and breakdowns occur with such maddening frequency’.[9]

(Fielding was eventually able to abduct a German post – Rodovani, 2 miles inland from Sougia - 6 months later, when he was evacuated on the 20 January 1944. Reports record that the post had 8 personnel – an Austrian and seven Italians, who were ‘induced to desert’.)[10]

The seventh and final contemporaneous reference in the Reports occurs in Tom Dunbabin’s report of the 8 – 23 September 1943 under the heading ‘Suggested Operations’.

‘I. Operation Muller. It should be easy to kidnap Muller. [11]One of our agents is on good terms with his chauffeur, and he might be abducted on the road. Alternatively it sounds easy to break into the Villa Ariadne with a strength of about 20. This operation, if carried out, should be synchronised with operation Brauer.’[12]

The agent referred to is Miki Akoumianakis, who played a key role in the eventual kidnap of Kreipe. Operation Brauer (General Brauer now being commander of the Western end of Crete) would be presumably led by Xan Fielding, who was at that time nine months into his second tour of duty and based in that area of Crete.

At the time of Dunbabin’s September 1943 report Leigh Fermor was in the central area of Crete, busy organising the evacuation of the Italian General Carta after the Italian armistice of 3rd September[13]. Carta embarked on the Motor Launch on the 23rd September 1943, with Leigh Fermor and Manoli Paterakis escorting him on board and with Dunbabin also at the evacuation beach at Dermati. The sea state was deteriorating and the commander of the ML decided that Leigh Fermor and Paterakis could not safely return to the beach – and so they inadvertently proceeded on to Mersa Matruh with the General. They conveyed with them Dunbabin’s report.[14]

[1] The National Archives. HS 5 / 723

[2] The National Archives. HS 5 / 723

[3] The National archives. HS 5 / 678

[4] The National Archives. HS 5 / 724

[5] The National Archives. HS 5 /728

[6] The National Archives. HS 5 / 725

[7] The National Archives. HS 5 / 725

[8] ISLD was the predecessor to MI6 and had infiltrated agents – Cretans, working as civilians - into the German Military command structure.

[9] The National Archives. HS 5 / 726

[10] The National Archives. HS 5 / 726

[11] Intriguingly there is a scribbled note to one side of the report in the National Archives that looks like Leigh Fermor’s handwriting stating ‘Kreipe’s predecessor’!

[12] The National Archives. HS 5 / 723

[13] The National Archives. HS 5 /728

[14] The National Archives. HS 5 /728